T’ai-chi chuan (also spelled taijiquan and taiji chuan) is an ancient Chinese martial art that comes in so many variations that it’s often confusing to the layman. Some styles can trace their lineage back to the founding of the art, while others date back to the early part of the 20th century.

T’ai-chi chuan (also spelled taijiquan and taiji chuan) is an ancient Chinese martial art that comes in so many variations that it’s often confusing to the layman. Some styles can trace their lineage back to the founding of the art, while others date back to the early part of the 20th century.

Some stress competition, while others emphasize health or self-defense.

The foundation concepts of t’ai chi ch’uan, which come from Taoism and Confucianism, go back to the beginning of written history in China.

They come from Lao Tzu’s monumental text, Tao Te Ching, from the I Ching and from various other health-promoting and breathing exercise treatises. The actual art can be traced back only 300 to 700 years, however. The founder is said to be Chang San-feng (Zhang Sanfeng), who is thought to have lived from 1279 to 1368, but no one knows if he actually existed. Some experts claim him as just being a myth, while others argue he did exist and there are monuments to him in China.

Many believed Chang San-feng was a Shaolin monk who decided to leave the monastery to become a Taoist hermit. On Wu Tang (Wudang) mountain, he gave up the hard fighting style he had learned and formulated a new art based on softness and yielding. One story tells how he had a vision between a snake and a crane (although some say it was a magpie, an eagle or a hawk). In theory, the crane should have had an easy time killing the snake, but in Chang’s vision, the crane would try to attack the snake’s head, and the snake would evade and hit the crane with it’s tail. When the crane would try for the snake’s tail, the snake would bite the crane. This resulted in the discovery of the basic tai chi concepts of evading, yielding and attacking.

Zhang Sanfeng

Chang assembled a martial art that used softness and internal power to overcome brute force. He is believed to have written: “In every movement, every part of the body must be light and agile and strung together. The postures should be without breaks. Motion should be rooted in the feet, released through the legs, directed by the waist and expressed by the fingers. Substantial and insubstantial movements must be clearly differentiated.”

This marked the beginning of tai chi chuan, but at that time it was called chang chuan, or long boxing after the endless flow of the Changjiang (Yangtse) River. Later, Chang formulated the 13 postures of tai chi.

While no one knows what his art looked like then, it is thought that the movements were practiced as individual techniques and/or concepts.

The next major historical figure was Wang Tsung-yueh (Wang Zongyue), who wrote the second tai chi classic and first referred to the art as tai chi chuan. He also coined the statement, “a force of 4 ounces deflects 1,000 pounds.” He is thought to have expanded the original 13 postures into a linked choreographed form. Some historians believe Wang actually founded the art, while others dispute his existence as well.

Chen Style

Another candidate for the role of tai chi founder is Chen Wang-ting. Some believe he created the art based on his military experiences, his study of local boxing methods and his gleaning of classical texts like Chuan Ching (Boxing Classics), which was written by Chi Che-kwong (Qi Jiguang) (1528 – 1587) as a compilation of known methods.

Chen Wang Ting

Chen developed several forms, and his family passed them along only to its members. At the 14th generation, around the late 1700s and early 1800s, Chen’s style spilt into the “old-frame” and the “new-frame” versions. The New frame was taught by Chen Yu-pen, and the Old frame by Chen Chang-hsing.

It was at this time that an outsider learned the art and started opening it up to the rest of the world. These days, students can learn several versions of the Chen style – including the old frame, new frame and modern forms- as well as off shoots which developed in towns located near the Chen family village. There are many variations of Chen style.

The Chen form requires the body to be straight and upright. Variations of the horse stance are emphasized. In the most popular version, which was taught by Feng Zhiqiang, the basic stance has the toes pointing outward slightly. Other forms use a parallel-foot horse stance. In all reputable versions, the knees are positioned directly above the toes. Most movements are executed with a sideways orientation – as if one’s opponents are standing to the side. The two of the most famous and highest level teachers today are Chen Xiaowang and Feng Zhiqiang who teach different versions of Chen style.

A novel part of the Chen style is the multitude of explosive movements: jumps, strikes and kicks. There is an emphasis on “silk-reeling energy”, or the spiraling energy that flows from the feet to the hands. Even thought the art is performed quickly, the practitioner should remain loose and relaxed. Any tension or disjointed movements mean it is being done incorrectly. It is difficult to practice the Chen style correctly because of the ease with which excessive force and muscle tension can creep into its movements. It may also be the reason the Chen style appeals to martial arts students who need a tangible sense of speed and force.

Yang Style

Yang Lu-chan (1799 – 1872) learned the old-frame style from Chen Chang-hsing. Many stories tell how this took place. A popular one holds that Yang wanted to learn the art, but the Chen family would not teach outsiders. So Yang took a job as a servant for the Chen’s and learned tai-chi by watching through a crack in the wall. Afterward, he would practice what he learned when he was alone in his room. One day he was discovered and asked to spar with the other students. He easily defeated all of them and was taken under the wing of Chen Chang-hsing, who then taught him the whole old-frame style. Yang is said to have spent the next six years studying under Chen. (Some historians say he studied for 13 years and others 18 years)

Yang Lu Chan

Yang eventually returned to his hometown of Kuang Ping (also spelled Guang Ping) and taught the old-frame Chen style. He later traveled to Beijing and became a military martial arts teacher for the Manchu government. After he altered the sequence of the movements in his form, it later became known as the Yang style.

Some modern practitioners claim that Yang watered down the art he taught to the Manchus and reserved a different version of it for his townspeople and family. But this may be just a selling point for those who insist they teach the only “authentic” form.

It is important to remember that Yang played a pivotal role in opening the once-closed art to the outside world. Two facts are significant: He learned the old-frame Chen style, and he was never beaten in combat. Even as a beginner, he defeated all of Chen’s students. For those who claim he didn’t learn all the secrets of the Chen family, this action speaks louder than any speculation. Because of his victories in challenge matches, he acquired the nickname “Yang the Invincible”. Nevertheless, he always avoided hurting his opponent in a match. Two of his sons carried on his art and family tradition: Yang Pan-hou (a.k.a. Yang Yu) and Yang Chien-hou (a.k.a. Yang Jian). The senior Yang also taught Wu Yu-hsiang and was friends with Tung Hai-chuan, who was the founder of pakua chang (bagua zhang) another major “Internal Style” of kung-fu.

Old Wu Style

Wu Yu-hsiang (Wu Yuxiang) (1812-1880) studied under Yang Lu-chan for an extended time. He then travelled to the Chen family village, and for three months he studied the new-frame style, with Chen Ching-ping. After that, Wu founded his own version of tai chi, which is now called the Wu style, the old Wu style or the “Orthodox Wu style”. This is a different family name and style than the Wu who studied with Yang Pan-hou and formed the “New Wu” form (described later). Some people call this form Hao Style after Hao Wei-chen.

Wu Yuxiang

Wu is responsible for the classic text titled Expositions of Insights Into the Practice of the 13 Postures. Wu Tu-nan, a master who lived to 107 years old, studied under Wu Yu-hsing and Yang Lu-chan, then developed his own form which influenced others teachers such as Tchoung Ta-tchen. Three major offshoots stemmed from Wu Yu-hsiang: the Li, the Hao and the Sun styles.

Hao Style

Li I-yu taught Hao Wei-chen (Hao Weizhen) (1849-1920), who then founded the Hao style of tai chi. This is a small-frame form, which means it uses tight small-circle movements and shorter stances. This is called small frame (Xiao Jia) and the Hao style name is often used for Old Wu form.

Hao Weizhen

In 1914 Hao embarked on a trip to visit a friend named Yang Chien-hou, who was Yang Lu-chan’s son and a major figure in Yang style. Hao ended up contracting an illness before he could find Yang. A well-known hsing-i master named Sun Lu-tang came to his aid, and Hao repaid him by teaching him his fighting style.

Sun was already renowned for his hsing-i ch’uan and pakua chang skills, but he decided to combine the Hao style of t’ai chi with the other two arts to form a new system called the Sun style, after Sun Lu-tang.

Sun Style

Like the Hao style, the Sun style is considered small frame. It employs many “step-ups” into its techniques, and this fact makes it somewhat similar to hsing-i. The Sun style also used short stances and straight leg kicks, but jumps have been taken out of its repertoire. It is said that the art melded pakua chang’s steps, hsing-I chuan’s leg and waist methods, and tai chi’s softness. This is often called the “lively paced” form (Huobu Jia). The Sun style was carried on by Sun’s daughter, Sun Jian-yun who teaches in China.

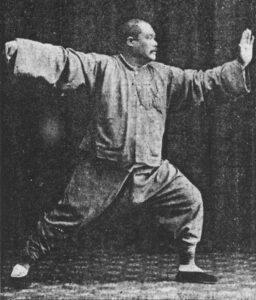

Sun Lu-tang (1861-1932) is also well-known because he was highly literate and a prolific writer. This made him a rarity among martial artists of that time.

Sun Lu Tang

He authored several books and in the late 1800’s popularized the term nei chia chuan, which translates as “Internal Family Arts” or “Internal Martial Arts.” The term Internal Martial Arts caught on and had a conceptual influence on other arts, which actually is different than the meaning of the term. The concept of Internal Arts referred to Arts developed within China such as Tai chi chuan , Hsing-I Chuan, and pakua chang. External arts are those based on Shaolin chuan which came from India. This idea often confuses people as they think it means having to do with “Internal power”.

New Wu Style

Yang Lu-chan’s two sons carried on his brand of tai chi chuan. One of them, Yang Pan-hou, taught a modified small-frame style. He is also reported to have taught a watered-down form to the Imperial family and still another form to his towns-people.

Yang Pan Hou

Several versions of tai chi are now attributed to Yang Pan-hou. The most famous is the other Wu style or “Medium Frame” form of Wu Jian-chuan (Wu Jianquan) (1870 – 1942) and another is Kuang Ping style (described later). Yang taught Wu Chuan-yu, who taught his son, Wu Jian-chuan. This style is called the “New Wu style” by some, and is distinct from the Wu style of Wu Yu-hsiang.

Some Wu stylists advocate using a pronounced lean in many of the techniques to help the student gain leverage and power. Other Wu practitioners remain upright as in the Chen style.

The original form had 108 to 121 movements, but several short and modified versions of Wu style now exist.

Old Yang Style

Yang Chien-hou (1842-1917) taught large-, medium-, and small-frame styles of tai chi. He was easier to get along with than his brother and had more students. One story told how he

Yang Chien Hao

Yang Chien Hou once held a sparrow in his hand and used his sensitivity to prevent the bird from taking off by neutralizing its push. In another story, armed only with a brush Yang is said to have defeated a martial artist who was wielding a sword. His sons, Yang Shao-hou and Yang Cheng-fu, carried on his art. Some of Yang Cheng-fu’s students originally trained under his brother, Yang Shao-hou. Consequently, they inherited the energy of that form.

Stories of Yang Shao-hou described him as being brutal and often injuring or killing his students. Consequently, he did not have many followers, but the ones he did have were good martial artists.

The well-known ones include his son Yang Chen-seng, Tian Shao-lin, Hsiung Young-hou, and Chang Ching-ling, all of whom carried on his unique small-frame method.

After Yang Shao-hou died, his students became followers of his brother, Yang Cheng-fu. Some tai chi historians claim that many of the senior students of Yang Shao-hou, believing their skill was higher than Yang Cheng-fu’s, went off on their own after Shao-hou died. Thus, they were written out of the official lineage, and some practitioners do not consider their versions of the art authentic.

Yang Cheng-fu style

Yang Cheng-fu (1883-1936) was one of the most important historical figures in modern tai chi chuan. He taught a “Large Frame” tai chi form that used slow, smooth, expansive movements. It was often said that he felt like a steel bar wrapped in cotton. Legend has it he was never defeated in combat. Chang Ching-ling an advanced student of Yang Shao-hou also practiced with him and may have helped develop Yang Cheng-fu’s skill.

Yang Cheng Fu

Yang Cheng Fu taught at the Central Kuo Shu Institute in 1926. When he moved south to Shanghai, he modified the Yang form, taking out the fast kicks and the more strenuous movements. He is also credited with emphasizing the health benefits of the art and popularizing it among the educated class. Yang deserved much of the credit for the current popularity tai-chi chuan and especially of the Yang style. Some claim he taught one art to the public and another to his closest disciples. Though many experts deny this idea. His form is referred to as “Yang Family Style”, as the “Family” designation is only appropriate for familial relations.

There are many more Tai Chi styles and forms in addition to the ones mentioned above. The numerous styles and forms of Tai Chi can be overwhelming to beginners and advanced practitioners alike.

Since the 19th century, the Chinese have understood the immense health benefits of Tai Chi, and its popularity has grown steadily. Now, Tai Chi is practised in almost every corner of the world. It is one of the most popular exercises today with more than 300 million participants. As we are surviving longer than our ancestors, chronic diseases such as arthritis and diabetes affect more of us, diminishing the quality of our lives. Increasing scientific evidence indicates that exercise is essential for prevention and management of these chronic diseases. Many studies have shown Tai Chi can deliver health benefits to help relieve disease and improve overall health and wellness.